Urban mining and its role in the clean energy transition

Article subtitle

A crucial part of mineral circularity

A crucial part of mineral circularity

Critical minerals and the renewable energy transition

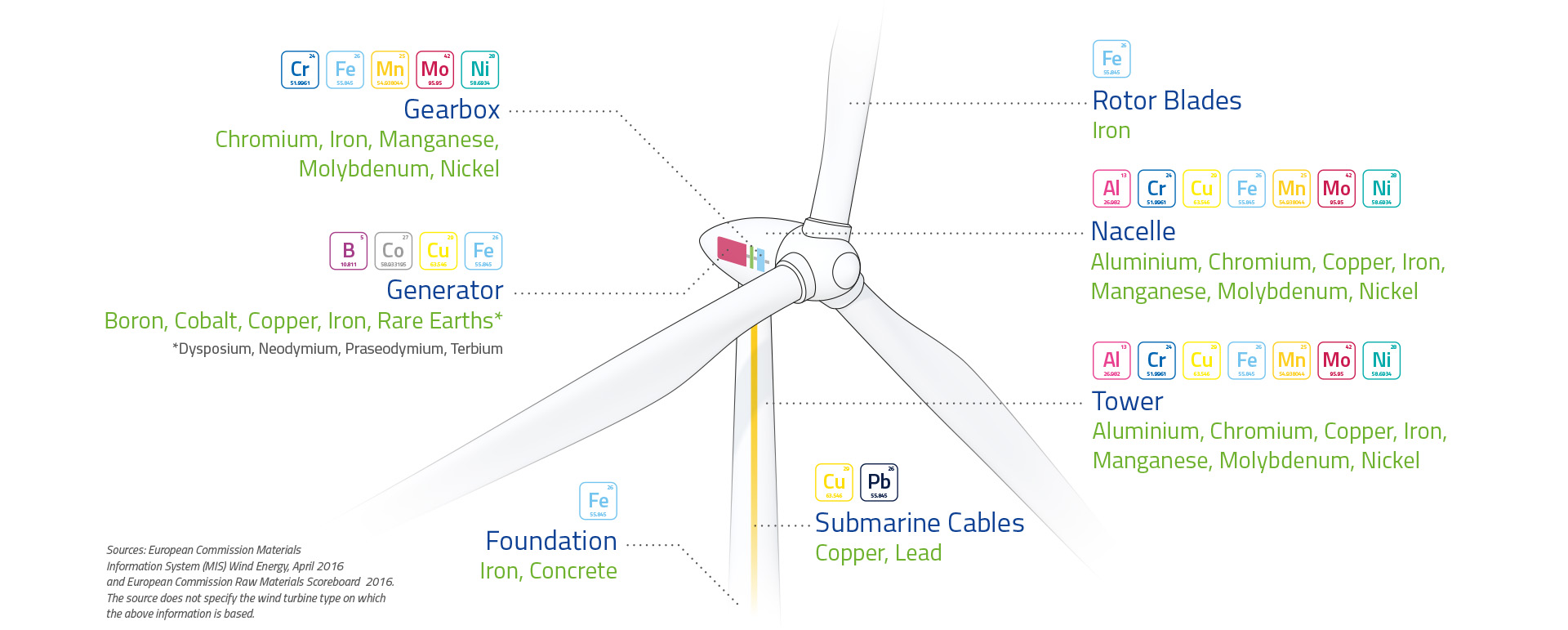

What do we see when we look at wind turbines? Maybe a futuristic silhouette towering above the fields and oceans. Or a grotesque giant structure invading the landscape. We may see it as proof of humanity’s inventiveness or a reminder of the looming climate crisis. What we don’t see in it are the rare, highly valuable elements that are mined all over the world to enable us to use clean energy.

Wind turbines, solar panels, electric cars, and other clean energy technologies require a huge supply of critical elements such as lithium, cobalt, nickel, graphite, and others. As the demand for this technology grows exponentially, so does the need for critical minerals. Conventional mining is still the predominant method of sourcing these minerals. Despite the environmental and geopolitical considerations associated with conventional mining, it continues to play an indispensable role in meeting the escalating demand for critical minerals. Acknowledging its inevitability, it is still crucial for us to reconsider our systems of production and consumption. Urban mining has appeared as one possible short-term solution to the problem of critical mineral supply.

Urban mining

Urban mining is the practice of extracting valuable resources from the vast amounts of electronic waste, discarded appliances, and other urban refuse. Urban mining repurposes the metals and minerals embedded in our electronic devices, cables, and infrastructure. It involves a meticulous process of sorting, dismantling, and refining, turning what was once considered waste into a valuable resource.

The potential and the pitfalls

Urban mining as a solution to the potential shortage of critical minerals is not without its problems. There is a gap between the huge potential of urban mining and the current practice of recovering minerals. Barriers of all kinds - economic, legal, technological, social, logistical, and managerial - all prevent us from closing this gap. From the economic perspective, mineral recovery from e-waste presents an attractive proposition, since the price of critical minerals contained in our devices is incredibly high. However, they are often present in such small, economically insignificant amounts that the cost of recovery surpasses the material value. From the technological point of view, design must play a more prominent role to ensure recoverable material is not lost when products reach the end of their lifecycle.

Urban mining isn’t the catch-all solution to the critical mineral demand we might hope for, but it is essential in redefining our way of thinking. By repurposing metals and minerals from discarded items, it challenges the conventional perception of waste and fosters a change in thinking toward a circular economy. It unravels the threads of our linear consumption patterns, enabling us to envision a future where resources are continuously reused, demand for virgin materials is lower, and materials are recovered through efficient recycling when appropriate. The complications inherent in urban mining underscore the need for innovative solutions, pushing us to overcome technological barriers and embrace a more sustainable approach to resource management.

Conclusion

For now, urban mining is a niche practice, with many limitations, but it presents a unique opportunity. Just as there was a gradual recognition of the need for clean energy, a realization is dawning that our current lifestyle is unsustainable. Urban mining is a vital step in applying the principles of a circular economy, offering a tangible example of how we can transition from a linear resource-use model. In addition to supplying critical minerals in the short term, urban mining can catalyze a shift toward a more circular future in our mindset.